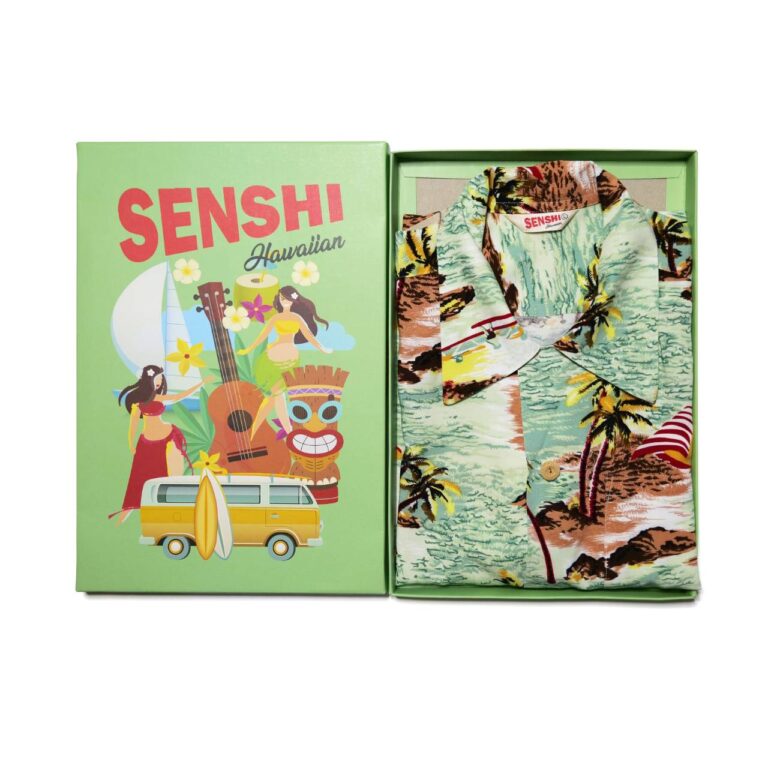

The reason why protesters wear Hawaiian shirts

Aloha shirts have become a disconcerting signature for members of a gun-toting, anti-government faction

IN THE PAST COUPLE of weeks, following the killing of George Floyd, curiously dressed counter protesters have attended scattered demonstrations across the U.S. Often armed and disconcertingly garbed in “Magnum P.I.”-style floral Hawaiian shirts, these men and women have gathered on the fringes of gatherings and marches in states including Texas, Georgia and Pennsylvania.

Who are these people and why are they dressed like tropical vacationers heading into battle? Mark Pitcavage, a senior research fellow at the Center of Extremism at the Anti-Defamation League based in Ohio, explained that deceptively cheery Hawaiian-style button-ups have come to signify extremists who believe that a second American civil war—or “boogaloo”—is on the horizon. Sharing rhetoric with far-right sects like white supremacists, militia groups and anti-government ideologues, these boogalooers, or “boogaloo bois,’’ have at times been a very small, but disruptive presence at overwhelmingly peaceful protests.

On Saturday May 30, after attempting to provoke violence at protests in Las Vegas, three self-identified members of the boogaloo community were arrested and charged with conspiracy to cause destruction. “Violent instigators have hijacked peaceful protests and demonstrations across the country, including Nevada, exploiting the real and legitimate outrage over Mr. Floyd’s death for their own radical agendas,” said United States Attorney Nicholas Trutanich in a public statement.

The boogaloo community trades information via social media sites like Facebook, message boards like 4chan and messaging services like Telegram. In a roundabout way, this decentralized approach to communication gave rise to the group’s peculiar name and choice of attire. The term “boogaloo” comes from the 1984 film “Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo,” which has long been the basis for a trite internet joke about imaginary sequels. At one point, the riff “Civil War 2: Electric Boogaloo” started being bandied about on far-right channels. As the ideology spread, the reference to “boogaloo” became contorted, variously appearing as “big igloo” and “big luau.” The Hawaiian shirt grew out of the “big luau” shorthand, according to several experts on far-right groups who were interviewed for this article.

There is some evidence that these linguistic twists were designed to fool social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram, which on May 1 of this year prohibited the word “boogaloo” when it’s accompanied by statements and images invoking or depicting violence.

Before the advent of the boogalooers’ Hawaiian-shirt predilection, the far-right “uniform” to achieve the greatest notoriety was the pressed khakis and polo (or button-up shirt) combination that white supremacists wore to rally in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017. This clean-cut look was a top-down dress code, predetermined by an organizing body in advance. It was calculated to distance participants from the cliched image of an “Aryan Brotherhood tattoo prison gang guy,” said Cynthia Miller-Idriss, a professor at American University and the author of “Hate in the Homeland”.

The boogaloo community’s Hawaiian-shirt dress code crystallized in a more organic, bottom-up way, emerging via a tangled web of internet humor and memes. Within fringe groups, this circuitous pathway from a meme to something more real is “a new phenomenon” said Ms. Miller-Idriss. As an earlier example of a meme that was elevated into alt-right iconography, she points to Pepe the Frog, a cartoon that in recent years was appropriated by racist and anti-Semitic groups and subsequently plastered on T-shirts, stickers and flags. The Hawaiian shirt reflects the diabolical sense of humor at the root of the boogaloo community. “Hawaiian luaus feature a pig roast, which is a slur for the police. So [the shirt is] also a way of evoking or suggesting violence in the coming civil war against the police,” said Ms. Miller-Idriss.

Plus, the inherent jolliness of a Hawaiian shirt gives heavily armed boogaloo boys a veneer of absurdity when they appear in public that can deflate criticism. “It’s tough to talk about the danger of guys showing up to rallies in Hawaiian shirts without sounding a little bit ridiculous,” said Howard Graves, senior research analyst at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala.

The Hawaiian shirt dates back to the early 20th century, when a Hawaii-based shirt maker of Japanese heritage began producing the ornately patterned designs. Aloha shirts were both birthed and popularized by people of color so their adoption, a century later, by a far-right militia can be viewed as dismally ironic, a white-supremacist act of appropriation.

Often, when an alt-right group has adopted a given brand’s clothing, that brand would issue a statement opposing this association. For example, in 2016, New Balance put out a statement denouncing white supremacy after a neo-Nazi blogger called the brand the “official shoes of white people.” The year after that, Fred Perry issued anti-racism messaging to counter the alt-right “Proud Boys” who had made its polo shirts their signature in the preceding decade. Yet, no single brand “owns” Hawaiian shirts, so there’s no obvious candidate to issue a statement opposing the boogalooers’ growing connection to these once-innocuous shirts.